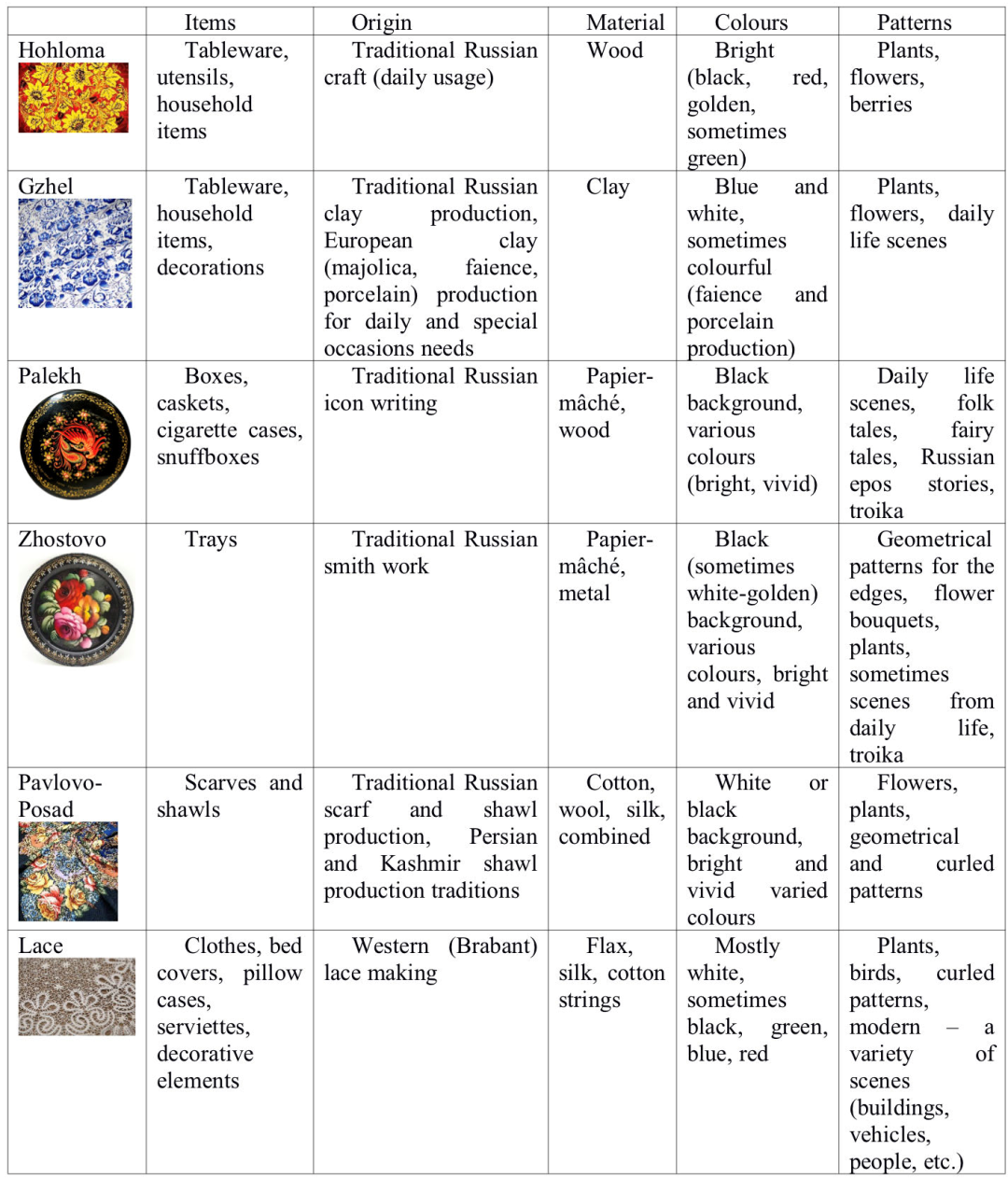

All these styles and craft areas have obvious similarities despite covering different areas of life. They all pay a lot of attention to natural elements and refle

ct nature to a great extent. The artists use contrast and warm colours (with the exception for Gzhel), there is vividness and calm repetition of motives, curliness of lines, and they all are applicable for daily use making everyday life more cheerful. The idea of making life more cheerful despite difficulties is one of the crucial components of Russian lifestyle since yoke period. Whatever the situation in the country is, Russians tend to brighten their life with cozy and vivid elements that are usually not for everyone to see. For this reason, all the colorful and cheerful elements that surrounded Russian families in their everyday life became popular abroad only in later Soviet era, when the Government was trying to create this image of Russians in the foreign surrounding by presenting these elements in international exhibitions.

For both Russians and foreigners, Russian crafts are reflection of the identity, but the accent is different. Russians see into depths and history of the crafts, for them it is a symbol of historical legacy, some of which is traced back to early years of Rus culture. Moreover, it was an element of something positive and bright to lighten up every day routine. With Russian culture and identity forged under some pressing, sometimes oppressing circumstances, the craft became a source of positive approach to life. Hence, all the bright and contrast colours, their variety and the variety of art elements and curliness of the lines. People, especially lower class, gradually implied this approach of treating life into their mentality – the outside can be shabby, but the inside should be cozy and positive.

For foreigners, Russian crafts give an idea about bright and light-hearted backbone of Russian identity. They see the top of the iceberg of Russian mentality without reaching the depth of historical legacy. This might be the benefit, as there is no need for an in-depth analysis of Russian culture. One, however, should remember that despite being culture of majority, the styles that are so popular, represent only part of Russian state nations, and, therefore, part of Russian state identity. It is a symbol of positive approach that Russians imply in their life, but it is also a symbol of complexity of the culture of Russian state, and differentiation of various cultures of Russian nations.

[1] А.С. Хорошев. Детские игрушки из Новгорода. Новгород и Новгородская земля. История и Археология. [08.03.2023] // https://bibliotekar.ru/rusNovgorod/70.htm?ysclid=lezebb80j4643257001

[2]Р.А.Мамбетов. Гончарное искусство в России. Другие методические материалы. [08.03.2023] // https://infourok.ru/goncharnoe-iskusstvo-v-rossii-4991061.html?ysclid=lezfkf1asu242123957

[3]Промыслы по металлу. Самобранка. [08.03.2023] // https://www.kp.ru/samobranka/narodnye-promysly/promysly-po-metallu/?ysclid=lezgj166v2513165056

[4] Мериновская матрёшка. Русские Ремёсла. 01.03.2020. // https://russianarts.online/193055-merinovskaya-matryoshka/

[5] Богородская резьба. Русские Ремёсла. 06.06.2015. // https://russianarts.online/612-bogorodskaya-rezba/

[6] № 140. Постановление Всероссийского Центрального Исполнительного Комитета. О мерах содействия кустарной промышленности от 26.04.1919. Собрание узаконений и распоряжений правительства за 1919 г. Управление делами Совнаркома СССР М. 1943 стр. 202-203. // https://istmat.org/node/35847?ysclid=lezizkaqkr889399560

[7] Н.Бедник. Хохлома Ленинград, «Художник РСФСР», 1980. Стр.17.

[8] Хохлома. Русские Ремёсла. 31.05.2015. // https://russianarts.online/193973-xoxloma/

[9] Н.Бедник Хохлома Ленинград, «Художник РСФСР», 1980. Стр. 3.

[10] Хохлома. Племзавод им. Ленина. 24.09.2016. // https://russianarts.online/89946-xoxlama-plemzavod-im-lenina/

[11] Гжель. Керамика 18-19 веков, Керамика 20 века. Издательство «Планета», Москва, 1982. Стр. 6.

[12] Там же.

[13] Гжель. Керамика 18-19 веков, Керамика 20 века. Издательство «Планета», Москва, 1982. Cтр. 24.

[14] Там же, стр. 38.

[15] Там же, стр. 70

[16] Гжель. Русские ремёсла. 09.07.2015. // https://russianarts.online/4356-gzhel/

[17] М.А. Некрасова Палехская миниатюра, Ленинград, «Художник РСФСР», 1983. Palekh Miniature Painting. Стр. 10.

[18] М.А. Некрасова Палехская миниатюра, Ленинград, «Художник РСФСР», 1983. Palekh Miniature Painting. Стр. 89.

[19] Палехская лаковая миниатюра. Русские Ремёсла. 16.07.2015. // https://russianarts.online/6789-palexskaya-lakovaya-miniatyura/

[20] М.А. Некрасова Палехская миниатюра, Ленинград, «Художник РСФСР», 1983 Palekh Miniature Painting. Стр. 250.

[21] Палехская лаковая миниатюра. Русские Ремёсла. 16.07.2015. // https://russianarts.online/6789-palexskaya-lakovaya-miniatyura/

[22] И. Богуславская, Б. Графов Искусство Жостова, Ленинград «Искусство», Ленинградское отделение, 1979. Стр. 5.

[23] Палехская лаковая миниатюра. Русские Ремёсла. 16.07.2015. // https://russianarts.online/6789-palexskaya-lakovaya-miniatyura/

[24] Там же.

[25] Палехская лаковая миниатюра. Русские Ремёсла. 16.07.2015. // https://russianarts.online/6789-palexskaya-lakovaya-miniatyura/

[26] И. Богуславская, Б. Графов Искусство Жостова, Ленинград «Искусство», Ленинградское отделение, 1979. Стр. 5.

[27] Тагильская роспись. Русские ремёсла. 03.08.2015. // https://russianarts.online/11366-tagilskaya-rospis/

[28] И. Богуславская, Б. Графов Искусство Жостова, Ленинград «Искусство», Ленинградское отделение, 1979. Стр. 6.

[29] Там же, стр. 9-10.

[30] Там же, стр. 15.

[31] И. Богуславская, Б. Графов Искусство Жостова, Ленинград «Искусство», Ленинградское отделение, 1979.

[32] Русские шали (Russian Printed Shawls), Москва, Советская Россия, 1986. Стр.5.

[33] Там же, стр.8.

[34] Русские шали (Russian Printed Shawls), Москва, Советская Россия, 1986. Стр.8.

[35] Там же, стр.6.

[36] Там же.

[37] Там же, стр.16.

[38] Там же, стр.13.

[39] Там же, стр.20.

[40] Там же, стр. 22.

[41] Текстильное дело. Русские ремёсла. [12.03.2023] // https://russianarts.online/home/textiles/

[42] В.А. Фалеева. Русское плетеное кружево (Russian Pillow Lace) Ленинград, «Художник РСФСР», 1983. Стр.20.

[43] Там же. Стр. 35.

[44] Там же. Стр. 38.

[451] Там же.

[46] Там же. Стр. 50.

[47] Там же. Стр. 69.

[48] Там же. Стр. 51.

[49] Там же. Стр. 142.

[50] Там же. Стр. 201.

[51] Музей кружева. Филиалы. Вологодский государственный историко-архитектурный и художественный музей-заповедник. [12.03.2023] // https://vologdamuseum.ru/content?id=131

[52] Вологодское кружево. Русские ремёсла. 05.06.2015. // https://russianarts.online/537-vologodskoe-kruzhevo/

[53] Карта народов. Народы России. [12.03.2023] // https://народы-россии.рф/?ysclid=lf4suvveie600093313

[54] Статья 3. Конституция Российской Федерации. [12.03.2023] // http://www.constitution.ru/10003000/10003000-3.htm

[55] Карта народов. Народы России. [12.03.2023] // https://народы-россии.рф/?ysclid=lf4suvveie600093313